On this day, 55 years ago, Star Trek was born; a franchise that represented the hope of what space—the final frontier—could mean for all of humanity. ILM has played a significant part throughout Star Trek history, including the creation of the first completely computer-generated cinematic image sequence in a motion picture. Read on to learn about other exciting work we’ve brought to life for Star Trek.

Nearly a year before Return of the Jedi wrapped production, Industrial Light & Magic began work on another famous space film: Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. ILM crafted many of the effects for the motion picture and even built scale models of both the ‘Enterprise’ and the ‘Reliant’: the first non-Constitution-class Federation starship ever seen in the series. As the script called for the Reliant and Enterprise to deal out significant damage on one another, ILM developed techniques to convincingly simulate the destruction without physically damaging the delicate models. Rather than move the models on blue screen during shooting, the VistaVision camera was panned and tracked to give the illusion of movement, a technique that ILM pioneered for the Star Wars trilogy, and further refined during seasons 1 and 2 of The Mandalorian. One of the most groundbreaking sequences of the film was ILM’s animation for the demonstration of the Genesis Device on a barren planet. The first concept for the shot took the form of a laboratory demonstration, where a rock would be placed in a chamber and turned into a delicate flower. Effects supervisor, Jim Veilleux, wanted the sequence’s size and scope expanded to show the Genesis effect taking over an entire planet; a challenge that ILM’s Computer Graphics group was up for. The team introduced the novel technique of “particle systems” for the sixty-second sequence, going so far as to ensure that the stars visible in the background matched those visible from a real star that was light-years from Earth. The animators hoped it would serve as a calling card for the studio’s talents. Their hard work paid off, as the group would later be spun off and become the foundation for Pixar Animation Studios.

For Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, ILM was tapped early in the production, allowing visual effects supervisor Ken Ralston and his team additional time to plan their shots. Leonard Nimoy credited the early involvement of ILM with expanding the creative input into the film’s design and execution. It became apparent to ILM early on that The Search for Spock required far more design and model work than had been required for The Wrath of Khan. The Earth Spacedock, for example, was a design intended to expand the scope of Star Trek. After approving a small three-dimensional maquette of the final design, ILM created a spacedock model that was over six feet tall. Rather than embarking on the painstaking process of wiring thousands of fiber optic lights, ILM had the innovative idea to construct the model out of clear plexiglass and then paint it. Once complete, the painted finish was etched-off in sections, creating the illusion of windows, with an inner core of neon light illuminating the resulting holes. The interior of the dock was simulated by an additional model that measured 20 feet in length, with a center section that could be removed. The interior illumination was generated by fiber optics and powerful lighting elements.

Finding himself in the director’s chair a second time for Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home—and building on the visual effects success found during production on The Search for Spock—Leonard Nimoy and the production team once again approached ILM early in development to help create storyboards for the complex optical effects sequences required. Many shots throughout the film were brought to life through matte paintings, both as a way to extend backgrounds, but also for establishing shots which greatly cut down on cost, compared to the process of building sets from scratch. Matte Supervisor, Chris Evans, attempted to create paintings that felt less contrived and more real, in stark contrast to the natural instinct of filmmaking which is to place important elements in an orderly fashion. Evan’s reasoning was that photographers would tend to “shoot things that were odd in some way”, and the final result would end up looking far more natural. The task of establishing the location and atmosphere at Starfleet Headquarters also fell to Chris and his team, along with famed artist Ralph McQuarrie, who had the daunting task of making San Francisco feel both teeming and futuristic, while still “of-our-world”. The scenes of the Klingon Bird-of-Prey on Vulcan were created through combinations of live-action footage—actors on a set in the Paramount parking lot which was covered in clay and used backdrops—matte paintings for the ship itself, as well as the rocky background terrain. The scene of the ship’s departure from Vulcan for Earth was more difficult to accomplish; the camera pans behind live-action characters to then follow the ship as it leaves the atmosphere, while other assets like flaming pillars and a blazing sun had to be integrated into the shot.

With Nicholas Meyer back at the helm for Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country, The majority of the visual effects again fell to the pioneering team of ILM, this time under the supervision of Scott Farrar (who had previously served as a visual effects cameraman on the first three Star Trek films), as well animator Wes Takahashi. ILM’s computer graphics division was called up again for the creation of three sequences, including the explosion of Praxis. Meyer’s idea for the effect was influenced by the immense wave hitting the ship in The Poseidon Adventure to inform the scale of their shock wave. To accomplish this, the team at ILM built a lens flare simulation of a plasma burst composed of two expanding disc shapes. They then layered-in swirling details that were texture-mapped to the surface. Farrar settled on the preliminary look of the wave, and graphics supervisor Jay Riddle used Adobe Photoshop on his Apple Macintosh to build the final color scheme for the effect. For the wave that hit the ‘Excelsior’, the ILM team pulled out all the stops, because in Riddle’s words, “this thing had to look really enormous.” The team manipulated two curved pieces of computer geometry, expanding them as they approached the camera’s view. Textures that changed every frame were added to the main wave body and then looped over the top of it to create the sensation of blistering speed. Motion control footage of the Excelsior was then scanned into the computer system and made to interact with this digital wave. The results were extraordinary. In fact, ILM’s ring-shaped “Praxis Effect” shockwave has gone on to become a commonplace feature in science fiction films depicting the destruction of massive objects.

As the franchise shifted back to television, ILM was once again counted on to deliver on their model-making and visual effects expertise, including the design and construction of the ‘USS Enterprise-D’ for Star Trek: The Next Generation. The models were exceptionally detailed, and included both two foot and six foot versions. ILM was also integral to the development of the “jump to warp” special effect, which was a cornerstone of the series throughout its nearly seven-year run.

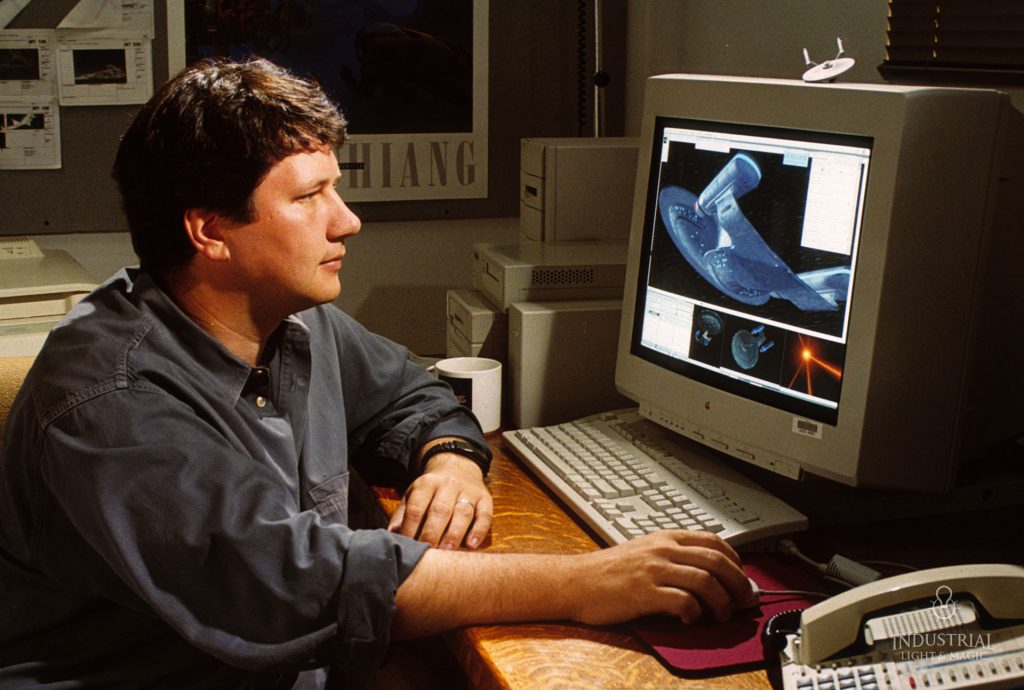

Anticipation was high for the legendary team-up of William Shatner and Patrick Stewart on the motion picture Star Trek: Generations, and ILM was up for the task. CG supervisor John Schlag recalled that it was easy to enlist ILM staff members who wanted to come and work on Star Trek, “it gave me a chance to be a part of the whole Trek thing, not to mention ILM is practically an entire company filled with Trek geeks”. Meanwhile, effects supervisor John Knoll’s team was charged with storyboarding the elaborate effects sequences. Previous Star Trek films had used conventional motion control techniques to film multiple passes of the starship models and miniatures on tracks. For Generations, the ILM artists began using computer-generated imagery and models for certain shots, a methodology that they were becoming well-versed in. No physical shooting models were built for the refugee ships, and other memorable CG elements included the solar collapses and the Veridian III planet. John Knoll and his team used a digital version of the ‘Enterprise-D’ for the warp effect, allowing them to keep consistent lighting throughout. While digital techniques were used extensively throughout the picture, ILM kept one foot firmly planted in its roots by way of the scale miniature of the observatory, built by model shop foreman John Goodson.

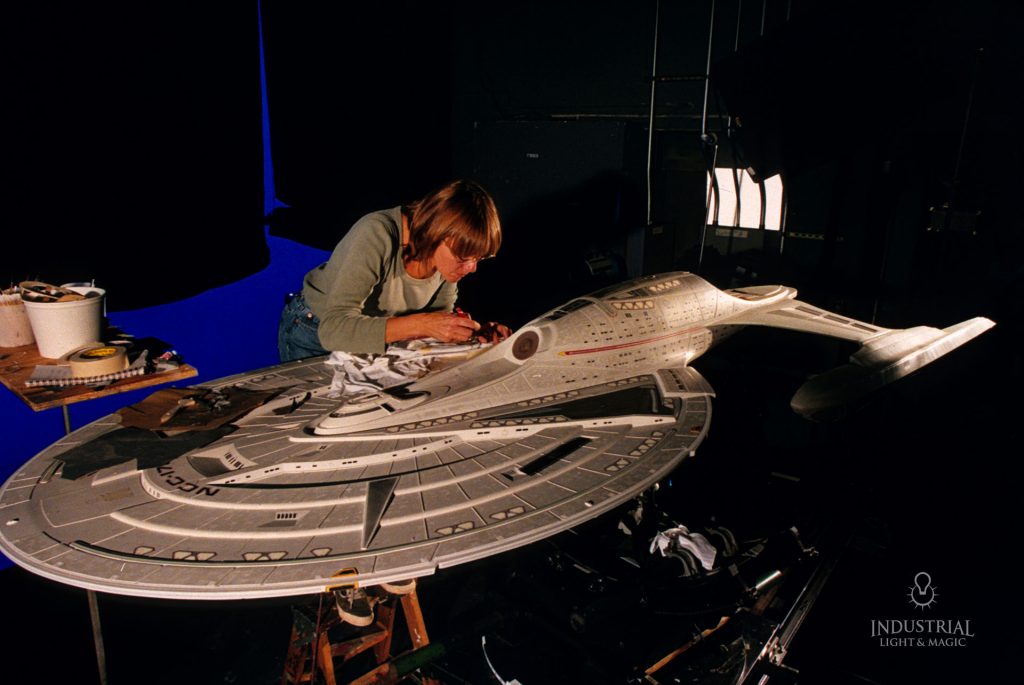

As Jonathan Frakes took up the reins on Star Trek: First Contact, ILM was brought on to develop the new Sovereign-class ‘Enterprise E’. Designed to be leaner, sleeker, and mean enough to answer any Borg threat that the Federation would encounter. ILM fabricated a nearly eleven-foot miniature over a five-month period. Hull patterns were carved out of wood, then cast and assembled over an aluminum armature. The model’s panels were painted in an alternating matte and gloss scheme to add texture. The team also cut the windows using a laser, and then inserted slides of the sets behind the window frames to make the interior seem more three-dimensional when the camera tracked past the ship. In previous films, Starfleet’s range of capital ships had been predominantly represented by the Constitution-class ‘Enterprise’ and just five other ship classes, but for First Contact, the team created five new ship classes. ILM VFX supervisor John Knoll insisted that First Contact‘s space battle show the full armament of Starfleet’s ship configurations. He reasoned, “Starfleet would probably throw everything they could at the Borg, including ships we’ve never seen before”. ILM was also tasked with imagining what the Borg assimilation of a Starfleet crew member might look like. Visual effects art director Alex Jaeger came up with a set of cables that sprang from the Borg’s knuckles and buried themselves in the crewmember’s neck. Wormlike tubes would burrow through the victim’s body and mechanical devices would break the flesh. The entire transformation was created using computer-generated imagery. The wormlike geometry was animated over the actor’s face, then blended in with the addition of a skin texture that was layered over the animation. The gradual change in skin tone was then simulated with shaders.

J.J. Abram’s Star Trek marked the first Trek film ILM worked on that was composed entirely of digital ships. Modeled by ILM’s Bruce Holcomb, the ‘USS Enterprise’ for this film was intended by Abrams to be a merging of its design in the original series and the refitted version from the original film. Abrams had fond memories of the revelation of Enterprise’s refit in Star Trek: The Motion Picture, because it was the first time the ship felt tangible and real to him. The iridescent pattern on the ship from The Motion Picture was maintained to give the ship depth, while ILM texture artist John Goodson artfully applied the “Aztec” interference pattern from The Next Generation. Goodson recalled Abrams also wanted to bring a “hot rod” aesthetic to the new Enterprise, which greatly influenced the end-design. Effects supervisor Roger Guyett also added more moving parts to the ship, including a new dish that would expand and move, as well as fins on the nacelle engines that would split when the ship would jump to warp. Carolyn Porco of NASA was consulted by ILM on planetary science and imagery. ILM’s technical team developed a new digital pyro tool allowing animators to realistically recreate what an explosion might look like in space: short blasts which suck inward, leaving debris from a ship floating. For the elaborate sequence of the imploding planet Vulcan, ILM used the same explosion tool to simulate its break up, allowing the animators to manually add layers of rock debris and wind swirling into the planet.

For J.J. Abrams return on Star Trek: Into Darkness, ILM contributed over 700 of the motion picture’s visual effects shots including the death-defying scenes of the volcanic planet Nibiru erupting in the opening sequence, the secret Federation ship, ‘Vengeance’, and its cataclysmic destruction as it crashes into the San Francisco Bay and tears through the city. ILM also created the iconic chase between Spock and Khan through the streets of San Francisco, the flying truck sequence, and also further refinement to the iconic ‘Starship Enterprise’. Guided by visual effects art director Alex Jaeger, ILM’s model, texture and lighting team created hundreds of buildings to fill out San Francisco, creating a living, breathing metropolis with a striking sense of design and vision for the future. As a nod to the importance that the team at ILM placed on Star Trek, the location of Starfleet’s San Francisco headquarters in the film was situated in the exact real-world location of ILM’s headquarters at the Presidio.

As we celebrate 55 years of Star Trek, it has been our honor here at Industrial Light & Magic to help filmmakers from across the franchise explore strange new worlds. To seek out new life and new civilizations. To boldly go where no man has gone before. So from all of us here at ILM, we extend a heartfelt Vulcan salute to the fans around the world: live long, prosper, and happy Star Trek Day!