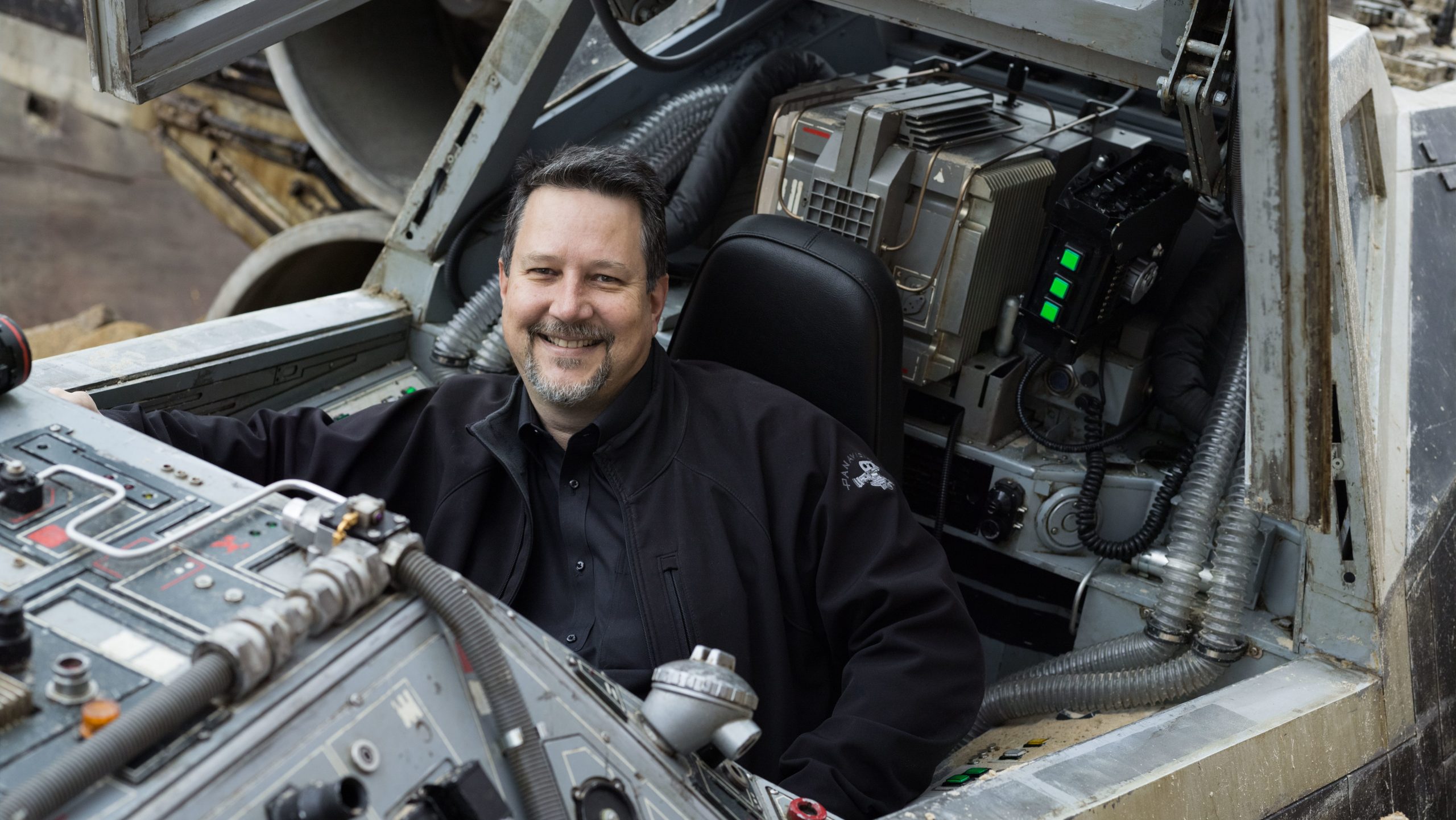

John Knoll, Executive Creative Director at ILM, and the Senior Visual Effects Supervisor on Rogue One: A Story Wars Story sits down with ILM.com to discuss the film’s five-year anniversary.

John, the whole idea of Rogue One started with you. How long back had you been thinking of this idea before it was greenlit?

I started thinking about this all the way back on Star Wars: Episode III – Revenge of the Sith. I was on set when we were shooting in Sydney, and I think we were waiting for some set-up to happen. I started chatting to Rick McCallum who was producing the film, and he mentioned that he and George Lucas were developing a Star Wars live-action TV series, and that they were working on scripts. I started thinking about all of the interesting tales you could tell in a show like that, and one of the first things that popped into my head was, “what about a Mission: Impossible-style operation to break into the most secure facility that the Galactic Empire had to steal the plans for the Death Star?” I started toying with that idea, along with a few others, and I approached Rick again to learn more about the time period they wanted to set the show in, and I realized that none of my ideas would apply to that period, so I shelved it.

When did it pick back up again?

Well, flash-forward to 2012 after Lucasfilm’s acquisition by The Walt Disney Company, where George selected Kathleen Kennedy to lead Lucasfilm, and our announcement of the continuation of the Skywalker Saga. What we also announced then that I was really intrigued by were the spinoff films. The first one we announced internally was Solo, and I got so excited about where these spinoff films could go, because the possibilities were endless. As a bit of a joke, I started pitching an updated version of my story that went, “picture a SEAL Team Six in the Star Wars universe, and they’re going on this desperate, high-stakes mission to break into the most secure facility in the Galactic Empire to steal the plans for the Death Star. What about that?” People would go “oh… actually, that sounds pretty cool…” [Laughs].

You can’t not love that pitch!

[Laughs] So I started having this conversation with a number of people, and every time I pitched it, I would start to add more detail, and it would get bigger and bigger. Kind of as a mental exercise, I asked myself, “well, if I were serious about this, who are the main characters? What are their arcs? What is the plot structure? How does this start, and how does this end?” I remember a specific moment where I was at this annual charity trivia game that we do, and I was on a team with a couple of friends, and we had about an hour over dinner while we were waiting for it to begin, and Kim Libreri said “tell me about this Star Wars story idea you have?” So I pitched him the half-hour version of it, with every detail, and at the end he goes, “you have got to go pitch this to Kathy.” At that point I realized I had to do this, because if I didn’t I would always wonder what could have been. So I called up Kathy and made an appointment, and I think it took maybe six weeks to find a time to meet with her and Kiri Hart from the Lucasfilm Story Group. I spent those six weeks writing up a really detailed treatment with all of the character descriptions. When the day came, I brought my treatment, sat down with Kathy and Kiri, and just dove into the pitch and the characters. They listened very politely to the whole thing, Kathy told me she was impressed with the story, and that was basically it. I didn’t hear anything for a few days, and at that point I was like, “well, I did it, at least now I don’t have to wonder.” A week later I got a call from Kiri, and she goes, “Kathy and I have been discussing your story a lot, and I think we want to proceed with this.” I was so elated, and one of the crazy things was that the first spinoff was supposed to be Solo, but Larry Kasdan got pulled into the development of The Force Awakens, and out of all of the spinoffs that they were tinkering with, Rogue One got slotted up to take its place in the queue. It was pretty surreal.

Tell us about the one-off cockpit shots in the film. I understand they were made from foam core, and then the CGI was built up around it?

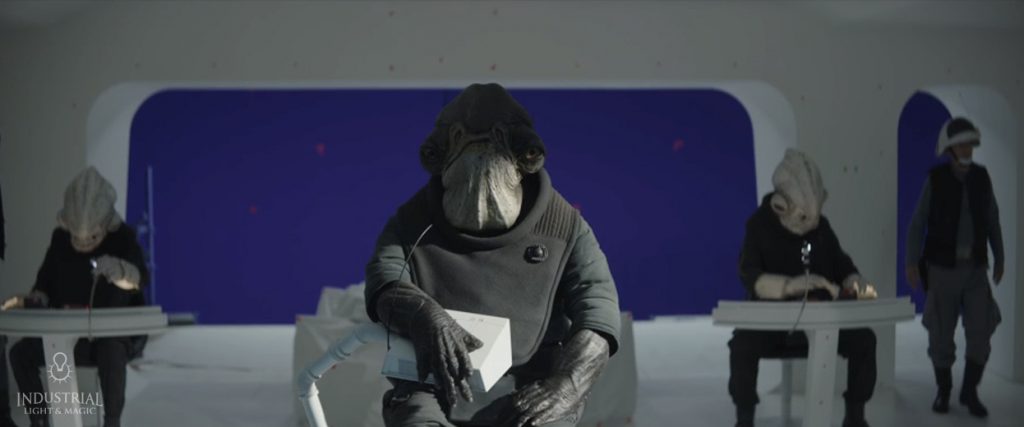

That’s right. I got talking with our Director of Photography, Greig Fraser, and our Production Designer, Neil Lamont, about some of these one-off sets – like the cockpit for Leia’s CR90 Corvette, the ‘Tantive IV’, or the interior of Admiral Raddus’ MC75 Star Cruiser, ‘The Profundity’. We looked at the set budget that we had, and realized that it was tough to justify an extensive build like that for something that would only be on screen for a handful of shots. The cost of entry for a Star Wars movie is expensive, because you can’t shoot a single frame of film without having to build almost everything in front of the camera. With that said, we were under a lot of pressure to trim wherever we could, so those limited-use sets hit the chopping block pretty early on. When asked how we could save money, I suggested that we could likely do them as virtual sets, where we just build a fragment of it where the actors were going to be. Greig Fraser had the same concern I did though, and that was that these types of sets are really hard to light well; not to mention that standing bewildered on a blue screen makes it hard for both the actor and the Director of Photography. Grieg and I came to the conclusion that we could use foam core – just enough to provide something to light, and something for the actors to get their bearings against. We felt it was a good way to go. Greig could get what he needed out of it, I could get what I needed out of it, and the actors could get what they needed out of it. That’s essentially how we did a couple of those sets, but the Art Department could not just make it out of foam core [laughs]. I told them it could be the sloppiest, slapdash thing, but they went ahead and added these nicely beveled corners, and it was all beautifully painted with lots of detail.

In conversations with Gareth Edwards early on, I heard that there were concerns that virtual sets might not look realistic enough. How did you convince him otherwise?

I did some fairly elaborate set recreations with some nicely rendered walkthroughs to build up Gareth’s confidence in the technology. Starting off, he wanted to build sets for everything, and that’s all fine on a production, until, of course, you can no longer afford to continue building them. I felt like we had reached a point where we had built a number of really good virtual sets for other projects, so we shouldn’t be so afraid of it. The topic of, “how do you light the actors?” became a talking point between Greig Fraiser and I. We both wondered what might prevent Gareth from embracing this, because he wouldn’t want an actor walking around on a blue stage – and I don’t want that either. So in the context of those conversations around lighting actors in virtual environments, that kind of led to what we did on the Blockade runner and Raddus’ ship. For some scenes that didn’t end up making their way into the film, I modeled the Death Star conference room, made famous in A New Hope, where Vader has his confrontation with Admiral Motti. The renders looked really good. I also modeled the corridor of the Blockade runner. Gareth felt strongly that we should do that one as a practical set, and I agreed, because it would be difficult to light the actors meaningfully because of all of the white balances. Resource-wise, the difference between building the foam core version of it, versus the practical set, was fairly insignificant, so it was hard to make the case that we should do it all virtually.

Going back to the prequels, did you also build a physical set in the corridor shot of Bail Organa’s ship, the ‘Tantive III’, for Revenge of the Sith?

We did, yeah. The Blockade runner corridors are pretty limited spaces with a lot of repeating patterns, so that shot in Revenge of the Sith, for example, wasn’t a budget-buster. But for Rogue One, as soon as you turn the corner and go into the cockpit, you have elaborate instrument panels with screens, and levers, and complex seats, and all of those sorts of things: that’s an expensive set, so it’s more cost-effective to do it digitally.

Did you create any other test environments for Rogue One?

I did make one final one, and that was a Death Star Docking Bay. I was really happy with the way the virtual set turned out, and the dynamic walkthrough. We added comms chatter, the sound of mouse droids, a bunch of small details to make the walkthrough immersive. It was a lot of fun to create. If we were to shoot Rogue One today, this type of environment, given its immense scale, would be the perfect candidate for Industrial Light & Magic’s StageCraft platform.

Speaking of StageCraft, what technologies were you and the team exploring on Rogue One that acted as a proving ground for what Industrial Light & Magic is doing today?

ILM’s LED volumes today certainly have their roots in what we were doing on Rogue One, and that actually came from a collaboration with Greig Fraser. About six months before principal photography, I had a really wonderful private session with him, where it was just him and I—no equipment or stages had been booked yet—and we sat down and I gave him my perspective on the top five obstacles that inevitably come up on tentpole movies.

I basically said, “sooner or later, someone in the production will want to shoot a daytime exterior scene on a soundstage. Here are the reasons why we need to push back on that.” I showed examples of it being done wrong, and examples of it being done right. I gave him a few other possible obstacles that we talked through, and one of those were scenes that take place in a moving vehicle. I knew that that was going to come up in Rogue One. Usually when we have a vehicle flying through a dynamic lighting environment, one of the commonly used gags is having grips put flags in front of the lights, which I find to be a little lackluster and unconvincing. It was at this point that Greig brought up, “well, what about using LED screens?” I actually had an experience with this a few years prior on Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol, where we did our car driving scenes by using the background plates that we shot in Prague that would then be comped out of the windows. We put them on LED screens and had them playing, and that provided the lighting for the scene, and it looked really nice. There was lots of lighting complexity as the car drove by different environments; neon signs, for example. You would then see the light move across the actor’s faces.

At this point, Greig and I then conspired to scale this idea up and build a stage, which was a like a proto version of our current LED volumes, and what we now know as StageCraft. It had the big cylindrical screen, the ceiling piece, and some ring panels to help surround it. The only difference was that we were not driving with real-time content like we do on StageCraft. We did pre-recorded content that was animatic-level CG, but it was photographically accurate, and the ratios were correct. So anytime you were looking over someone’s shoulder, and you saw what was on the screen, we had to replace it in post – but what we got out of it was very nice lighting. A lot of things seem obvious in hindsight, but it wasn’t until I was standing on the stage, seeing the light bounce off the shiny helmets and the cockpits, that I realized how big of a deal this was.

How did the actors react?

It was immensely popular with them. Instead of standing lost in a sea of blue, with someone saying “the bag guys are over there where that white ‘x’ is,” it was now all representative, so they could see it. It was really fun, it got them into character, and we got better results. And then that experience translated to Greig Fraser, when he was helping plan the first season of The Mandalorian with Jon Favreau and the Lucasfilm team, he was able to bring that entire experience over. “Let’s do this super LED volume. Let’s do what we did on Rogue One and then take it to the next level.”

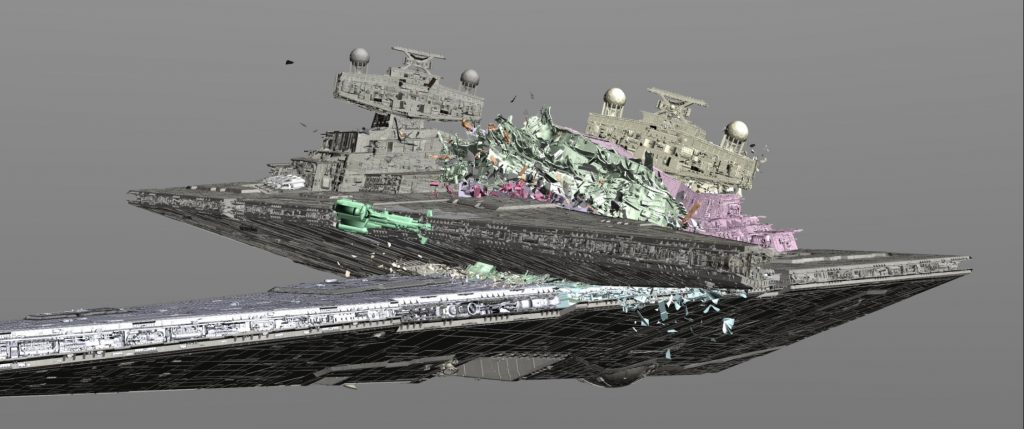

What was the genesis behind the Shield Gate situated above the Outer Rim planet of Scarif, and where did the idea come from to crash a pair of Star Destroyers into it?

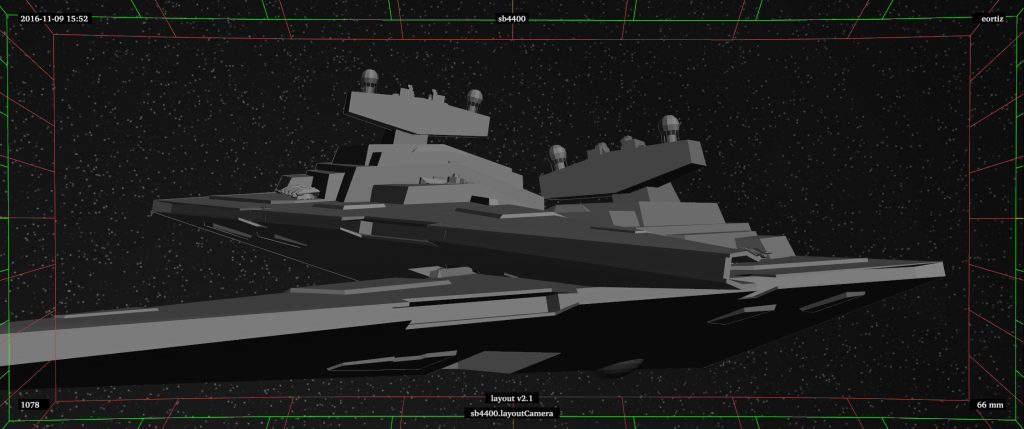

The Shield Gate at the Imperial security complex changed a number of times. In my original treatment it was an Imperial drydock and refitting facility for Star Destroyers, and the Rebellion would have mounted an audacious assault on the facility meant to act as a distraction. As the story developed, Gareth really felt that we needed to have the Shield Gate to prevent the Alliance Fleet from assisting the Rebels that were planet-side. As the rewrites were coming together, and the edit was taking shape, editorial was really focusing on the live-action elements that they were balancing, while the space battle would be further refined in post. They had a lot of placeholders in the edit at this point, “the Rebels arrive, they can’t get through, the action escalates, they take out some Star Destroyers, and then they open a hole in the Shield Gate”. The clock was ticking, and time was running out, so they asked us to mock something up based on the broad beats, so I came up with the idea to have the Rebels call up one of the Hammerhead corvettes to push a pair of Star Destroyers into each other, disabling them, and destroying the Shield Gate in the process. I wanted it to be really unique, so I started looking at footage online of what happens when container ships wait too long to brake and hit the dock, causing millions of tons of mass to just start plowing and plowing. Or when ships scrape into each other; just this kinetic energy. So scaling that up to a ship that is supposed to be a mile long, we asked, “how would that work?” If they were to push into each other, and you start one going, just pouring a bunch of energy and mass into that momentum. I wanted it to be all about mechanical damage; not just fireballs. Our Animation Supervisor, Hal Hickel, and his team, took that and ran with it, and what resulted was something that was really visually spectacular.

Is it true that the escape pods are visibly jettisoned during the shot of the Hammerhead corvette plummeting into the shield gate as it’s embedded in the Star Destroyer?

[Laughs] That is true. They survived! In my head canon, the crew survived. We put lifeboats on the Hammerhead in a pretty prominent way, and at one point we did have a shot of the escape pods jettisoning, but it became a bit distracting for what the point of the shot was. The idea is that they got out before it hit the Shield Gate.

The Hammerhead corvette originated in Star Wars: Rebels, correct?

It did, yeah. In fact, at one point, I went and met with Pablo Hidalgo from Lucasfilm’s Story Group, and basically asked him what types of ships might make up the Rebel Fleet at this point in history, that way we could start building them. If you think about it, there would be a lot of ships that would comprise the fleet at this point that you wouldn’t have seen in The Empire Strikes Back, or Return of the Jedi, for obvious reasons. A lot of them didn’t make it out. Pablo suggested the Hammerhead corvette, and I thought it looked great.

You also brought Hera Syndulla’s ship, the ‘Ghost’, over from Star Wars Rebels. What was the process like to bring a ship from animation into live-action?

We got the geometry for both the Hammerhead corvette, and the ‘Ghost’ from the animation folks. Owing to the medium, they were built at a much simpler level of detail, with some aspects being a bit caricatured for the animation style. We slimmed the ‘Ghost’ down, and made “the movie” version of it, with a fairly extensive detail pass.

Tell me about the kitbashing revival you did for this film?

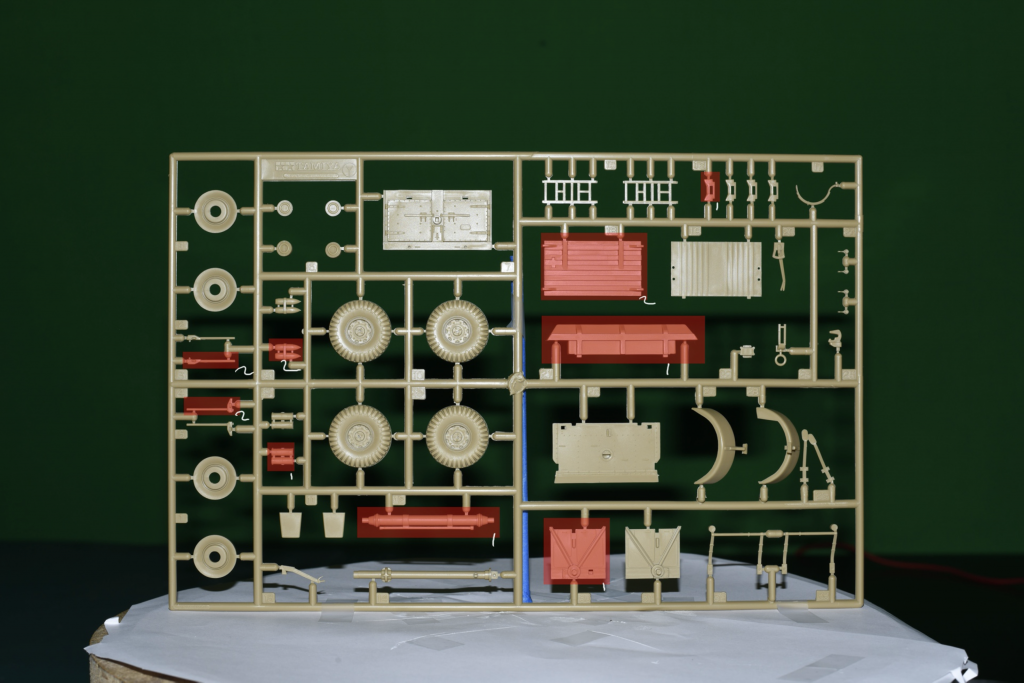

We had a lot of model shop veterans at ILM. John Goodson and Paul Huston were really helpful. Basically, I pitched this idea of building a Star Wars parts library, where we could essentially scan all of these model parts into a digital collection. Then we started to ask, “well, what are the right pieces? What are the right kits to pull from to give us the best bang of our buck?” The next step was actually sourcing these model kits. We set aside a budget and just bought a bunch of them on eBay; a lot of old vintage stuff. The Big Bertha howitzer, the Flak Wagon artillery gun, and a bunch of others that were used on the original films. We then photographed all of the sprue trees, and John Goodson went through and circled all of the ones we needed. We then laser scanned them all, and a partner of ours, Virtuous, then built really nice, optimized versions of all those pieces. That then became the basis of our Star Wars kitbash library, which we have gone on to use throughout the rest of the Star Wars projects we’ve done. For The Last Jedi, Roger Guyett’s team expanded the library even further with more model kits scanned in.

Tell me about how you captured the look of the original miniatures?

A lot of it had to do with kind of making the model pieces look wonky, if that makes sense. If you’re putting a bunch of greebles in a row, don’t make them all perfectly straight. Turn one two degrees, and give them all a bit of jitter. Maybe break some of the edges so they’re a bit crooked and less perfect. The tendency is to think that a mile-long ship should be precision-made, but if you look at a real aircraft carrier up close, the hull has a little wobble in it, because it’s hard to make big stuff like that super precise. You can see it in the miniatures at the Lucasfilm Archives too, lots of wobble, and things where the greebles are misaligned. If you don’t have that imperfection in there, your eye will see it.

Were there conversations around trying to match the lighting of A New Hope on the miniatures?

Oh yeah. In fact, there was a philosophical discussion around to what degree we would match how the miniatures were lit. For the original trilogy, the miniatures were lit with stage instruments that were maybe twenty feet away, and that implies a certain spread angle on the light, and the size of the penumbra on the shadows. So the question was, “do we want to light these ships like there is a correctly scaled up 10K light that’s three miles away from them, preserving that original look, or do we want to light them from a sun that is one hundred million miles away, so the rays are more parallel?” Though it was tempting at times to go the other way, we ended up pushing more into the realism; same goes for the planets. We did very realistic renderings of the planets, which gave it the look and feel of the photography you might see aboard the International Space Station in orbit.

Tell me about how you brought Red Leader (Garven Dreis), and Gold Leader (Jon “Dutch” Vander), from A New Hope, played by Drewe Henley and Angus MacInnes, respectively, back into the film?

If you think about it, we’ve brought back a number of characters, and we used every technique to do it. From A New Hope, Cornelius Evazan, Hurst Romodi, and Jan Dodonna were recast. Mon Mothma, from Return of the Jedi, was a recast (though Genevieve O’Reilly played Mon Mothma previously in a deleted scene from Revenge of the Sith). The creature shop brought Ponda Baba back from A New Hope. Anthony Daniels played C-3PO again. We brought R2-D2 back. Chopper was brought from animation into live-action. Jimmy Smits returned to play Bail Organa from the prequels, and James Earl Jones voiced Vader again. We of course had Grand Moff Tarkin and Princess Leia which were full computer graphics. Incorporating the unused footage of Red Leader and Gold Leader though was that final technique. That was discussed very early on about how this film is going to meet right up with A New Hope. We thought about how a lot of these people in the Battle of Scarif would have participated in the Battle of Yavin too, so we should see some familiar faces. It was hard to avoid Red Leader and Gold Leader, so we decided to look through all of the dailies from A New Hope to see if we can find anything. It was super fun to do, but it was harder than it looks, because the lighting style was pretty different back then. The footage was really grainy and had faded, so trying to get a shot from forty years earlier and drop it into the film without it looking “off” was a challenge. We de-grained it, and did loads of rotomasks. The orange color of the flight suits had to be boosted.

[Laughs] One thing I discovered during this process, was that the digital X-wing cockpits we created were true and faithful to what the exterior looked like; I never noticed it before, but the cockpits that George had created had some huge cheats in their interior dimensions. The back window, for example, was made very tall so that George could get the shots looking over Luke at R2-D2. Ours didn’t match that at all, and it would have been jarring to jump between the digital cockpits and the archival cockpits. We had to rotoscope around Red Leader, and then insert him into the digital cockpit.

We actually did it in reverse for Gold Nine, piloted by the character of Wona Goban, and played by Gabby Wong. She was shot in an X-wing, but we really wanted the Y-wings to be firing the ion torpedoes. Instead of creating a Y-wing cockpit from scratch, we simply rotoscoped her into the archival footage of the Y-wing cockpit that we had.

Red Five made an appearance too.

He did. There had to be a reason Luke was assigned Red Five in A New Hope [laughs].

Was there a discussion about including Wedge Antilles at the Battle of Scariff?

We discussed whether or not he should be in the battle, yes. But Wedge has that great line in A New Hope, “Look at the size of that thing!”, so it’s implied that he’s never seen the Death Star in person. We wanted to preserve that. Matthew Wood and Skywalker Sound actually brought in David Ankrum who overdubbed the voice of Wedge Antilles (played by both Denis Lawson and Collin Higgins in A New Hope) to voice Wedge again. If you listen to the comms chatter when the fleet is being scrambled, that’s Wedge telling the flight personnel to report and redirect to Scariff.

Tell me about Grand Moff Tarkin and Princess Leia. Were they always intended to be a part of this specific story?

Tarkin was in my first treatment, and that conversation happened really early. I also really wanted to end the film with Leia. As the script was progressing, Kiri Hart told me that they wanted to prominently feature Tarkin, and asked how I felt about doing it. For Mon Mothma, the recast was perfect, because everyone remembers her lines from Return of the Jedi, but they don’t have a super clear picture of her in their head. They remember her robe, and the medallion she’s wearing, and her red hair, but if you recast and match those things, someone that looks a lot like her could fit into the role. Tarkin and Leia are so iconic, that you couldn’t do that with them. If they’re going to show up, you’d have to really match their likeness, and the only way to do that is with computer graphics.