The cinematographer for Denis Villeneuve’s Dune, and Matt Reeve’s The Batman, joins Industrial Light & Magic’s Publicity Group to discuss his work on Rogue One: A Star Wars Story. Greig shares how the early Kenner action figures inspired his love of Star Wars, and the influences he found in 1970s cinema, the works of Andrei Tarkovsky, and the film The French Connection.

What was your introduction to Star Wars?

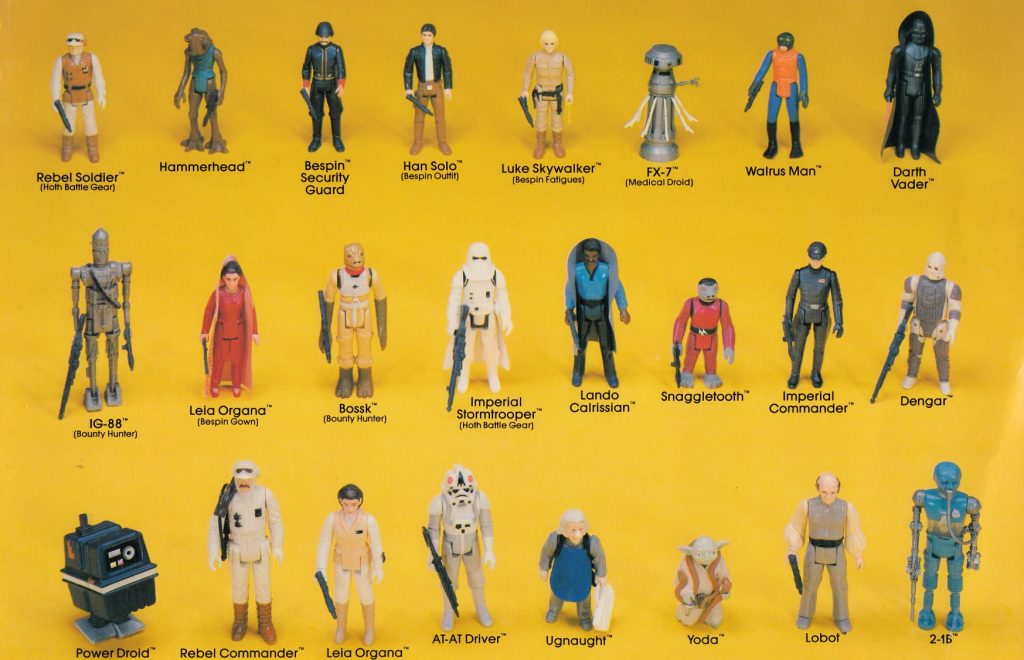

If I think back about how I was first introduced to Star Wars, I think it had to be through the toys. I genuinely think it was the toys that got me going there. I was two years old when Star Wars came out, and five when The Empire Strikes Back premiered. You couldn’t really call me a “film fan” at that point, but the franchise definitely existed in my universe. I read some of the comics later on, but the thing I loved the most back then were the toys. A few years after, I think ‘82, Star Wars came to Betamax and VHS, and then the year after that, in 1983, I finally saw Return of the Jedi in theaters. It was mind-blowing, because the visual effects that ILM did for it were so revolutionary and groundbreaking. Then over the course of the next ten or fifteen years, I think I watched A New Hope, The Empire Strikes Back, and Return of the Jedi literally hundreds of times.

How did the experience of watching the original trilogy influence your work on Rogue One?

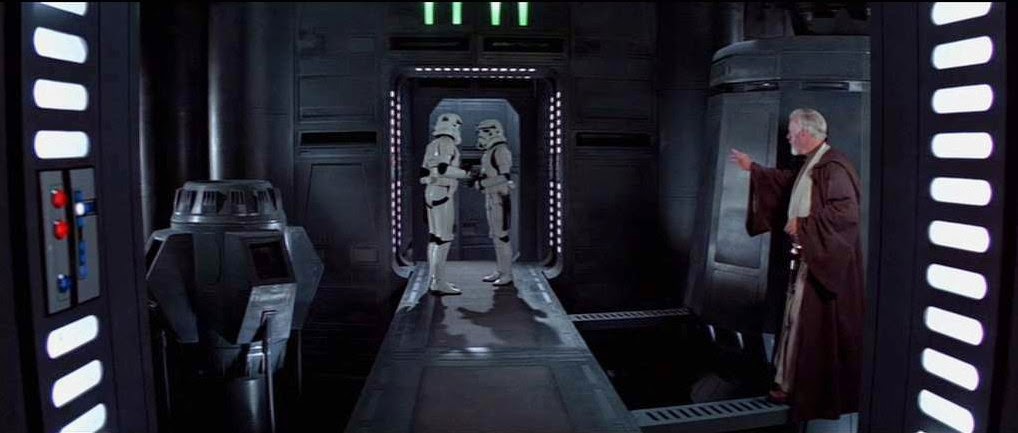

The funny thing is, when it comes to Star Wars, there is a very particular visual language with the way the films are made. From the way they climb aboard the Millennium Falcon, to the wide shots of the Millennium Falcon going past the camera. There is a visual language that exists that, unless you’re studying it, you don’t really notice it. That occurred to me when we started Rogue One, when Gareth basically told me, “we’re not remaking Star Wars. We’ll make this movie the way we would want to make this movie.” But the thing is, what was great about that, is that we could channel Star Wars. Normally you try to hide your influences; you don’t wear them on your sleeve when you make a movie. You try to become a little more nuanced, a little more “clever” about sort of fooling people into what your influences are. “No, I didn’t actually watch Steven Spielberg films to make this ‘Spielbergian’ movie.” Those sorts of things. But what was great about Rogue One is that we were making a film that actually connected directly into Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope, by design. So if we wanted to reference anything from Episode IV, Episode V, or Episode VI, we could. We were actively encouraging ourselves to do it. For me that was a huge revelation, because normally, on any other film, you wouldn’t do that. For example, when we went back and watched Obi-Wan’s sequences aboard the Death Star, we would study how Sir Alec Guinness would move throughout the corridors, and it was very influential in the way that we did some of our movement through the Imperial security complex on Scarif. We took for granted that it was such a big place, and that the Imperials would be minding their own business and doing their own thing, and that you could have these Rebel spies, and have them actively infiltrate this heavily-fortified complex.

Was there a lot of conversations around trying to match the aesthetic of A New Hope?

There was. Growing up, you got used to watching Star Wars on Betamax and VHS, on a home television format. For research for this film, I was able to watch a 4K scan of one of the earlier films, and the conversation turned to, “is that our North Star? Do we make it look exactly like that? Do we shoot it on film, with those same lenses?” Sometimes your memory of something can be slightly different from reality, so what we did for Rogue One, is we tried to match it to the aesthetic of our “mind’s eye”, and what we remember from Star Wars growing up. For us, thinking about that look – it wasn’t super sharp, but it had depth and clarity. It was soft at times, but not defunct. That is why we chose the format that we did, the ARRI ALEXA 65, paired with these old lenses. For Gareth and I, it felt like it was showing us the film that we remembered as kids.

Did you find other advantages to shooting digital? Was there ever a conversation of shooting it on film?

There were a number of factors. The look we were trying to achieve was one factor, but the other thing that we had to balance towards was the fact that Gareth Edwards is a very hands-on filmmaker. He loves to operate the camera. Watch his film Monsters, which, coincidentally, was the whole reason I wanted to meet Gareth in the first place. When I was called up to do the interview for Rogue One—and of course, I was so excited for the opportunity—I thought, “even if I don’t get this job, I will get to meet the guy that made Monsters. I’ll get to shake his hand, and I’ll get to tell him about the mad respect I have for him and his film.” So when he explained to me that he wanted to make Rogue One with the same spirit that he used to make Monsters, I got really excited. That decision was also part of the reason we chose the ALEXA 65. It had all the film qualities of a much bigger camera, but it was in this bitesize package that you could throw around, and put in cockpits, without having to destroy too many things to get the shot you needed. It was a series of factors, but it all worked in our favor.

Gareth has a unique style of shooting, where he’ll go from one take to the next without slating. How did your style integrate with that?

I found it very exciting. In some ways, even though Gareth was my director, he was also my camera operator. I loved helping him build a world where he could achieve anything that he wanted to achieve; be that handheld shots, or very specific tracking shots. That’s what I loved about Rogue One, and how Gareth wanted to make it. There were considerations, of course, but there were moments of freedom – both in freedom of movement, and freedom of camera. It kept everyone on their toes. He would pick up these small moments, maybe something an actor was doing, and he would get the camera in there and capture it.

Greig, your photography has such a distinct style. What influences did you pull from in designing the palette of Rogue One?

I’m a big fan of world cinema, and I’m a big fan of ‘70s cinema. I love Andrei Tarkovsky. I think the way that he makes movies is so beautiful, and so strong. But I also love the way that Kathryn Bigelow shoots her films. I love The French Connection, and the way that it was shot. For Rogue One, we mined the depths of our interests, and the types of films that we loved to watch. Lawrence of Arabia was another influence. These massive, David Lean-style battles. These big frames, and tracking shots, and static shots. Then you combine that with modern-day filmmaking, which, if you look at the evolution of cameras, has changed drastically. Back in the 1950s and ‘60s, the cameras were much larger than they are today, and harder to move around. Therefore, films looked a certain way. When you get into the 1970s, when George Lucas was shooting Star Wars, there was not a lot of handheld in that film either. The cameras were not really malleable, and, stylistically, that wasn’t really what he was after anyway. What was good for us though is that we were able to combine our interests and influences. Gareth and I clearly love Star Wars, but that is not the only thing we’re influenced by. French cinema, documentaries, all of that played a part for us.

Tell me about the early conversations around virtual production and LED walls on Rogue One, and how that got us to today with ILM’s StageCraft?

This is where having amazing partners, like Industrial Light & Magic and John Knoll, was very integral. What we were pitching was not a common thing. Emmanuel “Chivo” Lubezki had played around with something similar on the film Gravity, with putting actors in an LED box, but we were talking about putting people into ships and big environments. It all stemmed from a lighting problem, and the problem goes like this: “you’ve got somebody in an X-wing above a planet. We’ll use Earth as our stand-in for Scarif. You’ve got a sun source, you’ve got ambient light bounce from Earth, and then you have black space. When you’re in the atmosphere, you have all of this beautiful light coming from above, and below, and from your sun source. That type of scenario is really easy to light. But what happens when you’ve got no ambience above, some ambience below, and then a sun source? Now, imagine those lighting conditions, and pretend you’re in the cockpit of that X-wing, and you do a barrel roll. As you spin around, it’ll transition from light to shadow on your face and around the cockpit. To try and do that in a studio environment, with the lighting we have, is very difficult. You have to put diffusion on all sides to make it nice and soft, so when you sequence the lights over the top, you get the illusion of camera and lighting movement. But what happens when you push light through the diffusion? It bounces back from the other side. With that said, I needed a black side and a light side, but then, of course, that wouldn’t have worked for the barrel rolls, because the light would have needed to move. The one thing we had at the time that could account for all of this were LED screens. When the light turns off on an LED screen, it’s pitch black. It’s the perfect lighting tool for that type of thing. That then progressed into the next question, “if we’re going to use that tool, for that one instance, can it work for other scenarios? Like flying across Jedha, or soaring through the atmosphere of Scarif?” That’s where this tool, this LED volume, became immensely helpful. People like John Knoll, and the people at ILM, are extremely integral to getting the quality right for something like this. Good VFX can live or die by bad lighting. That’s why ILM’s StageCraft is such a powerful tool for DP’s. Because DP’s know, if you can get the lighting right, you’re halfway there to getting a good final image.

That must have been exciting to figure out?

It was such a great project, because it really upheld the vision that George Lucas had for the future of filmmaking, the “stage of the future”. George theorized that, years down the road, there might come a time when a filmmaker could walk onto a stage, and they could project whatever they wanted up onto the walls, or that those walls could have color-changeable light. They wouldn’t have to light for it, they’d only need to flick a switch. That was the hopeful future that George was thinking about, and now, years later, ILM made that a reality with StageCraft. Filmmakers now have the ability to put any high fidelity, real-time image up on the LED volume. Rogue One was the proof-of-concept for lighting, and that evolved into what ILM, John Favreau, and the Lucasfilm team are doing on The Mandalorian, along with so many other exciting projects.

George referenced a lot of things for his aerial combat, including old WWII gun camera footage. How did you approach the ships flying in Rogue One?

While we were shooting, it became obvious where the camera could be, and where it couldn’t be. In Star Wars, there were never any mid-shots of people sitting in cockpits. You don’t have Han Solo in a mid-shot, shooting from outside of the cockpit. You never had a camera floating in space for a shot like that. The camera was always fixed inside the cockpit, or super-wide. There was no in-between. It would never go from a super-wide, into a mid-shot, into a closeup. The only example of that might be the final shot of the Millennium Falcon, just before Lando departs the Medical Frigate, at the end of The Empire Strikes Back. With that said though, we tried to maintain those parameters for Rogue One, and we didn’t want the audiences to have to think about it. I haven’t spoken to George Lucas about it personally, and maybe if he would have had infinite resources he might have shot it differently, but we wanted our film to match A New Hope, and we loved the look. It built our visual understanding of what a Star Wars film should be.

There’s something intimate about it. When I think about old WWII air combat movies, they did the same thing.

Exactly. And they were forced to shoot like that. You either had a camera in the cockpit, or a camera on another plane. You couldn’t get a plane in close enough to get a reaction from a pilot, or you’d have planes crashing into each other. It was either super-wide, or close. It was purely pragmatic.

You did have a unique shot that was used a few times that I loved, and that was the one of the camera fixed on the X-wings and Y-wings, directly behind the astromech droid.

Gareth was clever, because even though we had these rules on how we would shoot the ships, we would work off moments from the earlier films to devise new things. There’s that shot of R2-D2 getting blown up in A New Hope by Vader in the Death Star’s meridian trench, and this was kind of an evolution of that shot, while still keeping one foot planted in that A New Hope aesthetic.

How did it feel with The Force Awakens shooting alongside your film, and to a degree, The Last Jedi too, when you were shooting pickups?

It was fun. We were all sharing buildings and in each other’s worlds. I’m such a big fan of Star Wars, and I could have walked on set and spoiled everything for myself, but I chose not to. I just wanted to enjoy them as a fan. I did have one thing spoiled for me… someone walked up and told me the scene regarding Han Solo, and my first reaction was, “how dare you do that to me! I wanted to see that in theaters!” [laughs]. We shared some crew from time to time, but we generally had blinders on for Rogue One. While they were making their films in the Skywalker Saga, decades in the future, we were leading right into A New Hope, so ours was almost the equivalent of a period film, in our language. I found that to be very exciting.

What’s your favorite shot, moment, or sequence in the film?

One of my favorites is that wide tracking shot of Jyn Erso (Felicity Jones) making her way through the Massassi outpost on Yavin 4 after she’s “rescued” from the Wobani Labor Camp. I also love the final sequence with Vader aboard the ‘Tantive IV’. When Gareth rang me to tell me we were going to do that, I was ecstatic. It’s such a wonderful sequence. We had the time to prepare it properly. We had the time to rehearse all the action, and to do the lighting tests. We also spent a lot of time figuring out how best to light Vader. As a kid in a grown man’s body, that blew me away. Vader, this dark “shape”, terrified us as kids. It was a dream come true to add to his iconography. I felt very honored and very blessed. Another moment I loved was seeing the full-sized X-wing props in person for the first time. I was transported back to being a kid again, playing with my toy X-wings, but then, of course, my filmmaker brain would kick on, and let me tell you, moving full-sized X-wings around on a set is pretty difficult [laughs].

I love the sequence you shot in Iceland of Orson Krennic and the Death Troopers making the long trek up to the Erso homestead from the shuttle. His cape flapping in the wind, it was incredible.

I love that shot too. An interesting thing about that sequence is how we found that location. In that part of Iceland, there’s all of this black sand, so they plant this weed to prevent it from blowing onto the roads and destroying the cars. It’s basically useless outside of keeping the sand from blowing about. We found that location on Google Earth while we were driving around, location scouting. I thought it looked so unusual and interesting. As soon as we dropped the moisture vaporators in, those weeds started looking like crops that the Erso’s were farming, and it instantly became Star Wars.